White Magic

Ebony and ivory harmonize in Hemphill group show. Also: Patterns and illusions, Hecht’s light works, Lukaszewski’s elegant tangles, Hwang serves up abundance

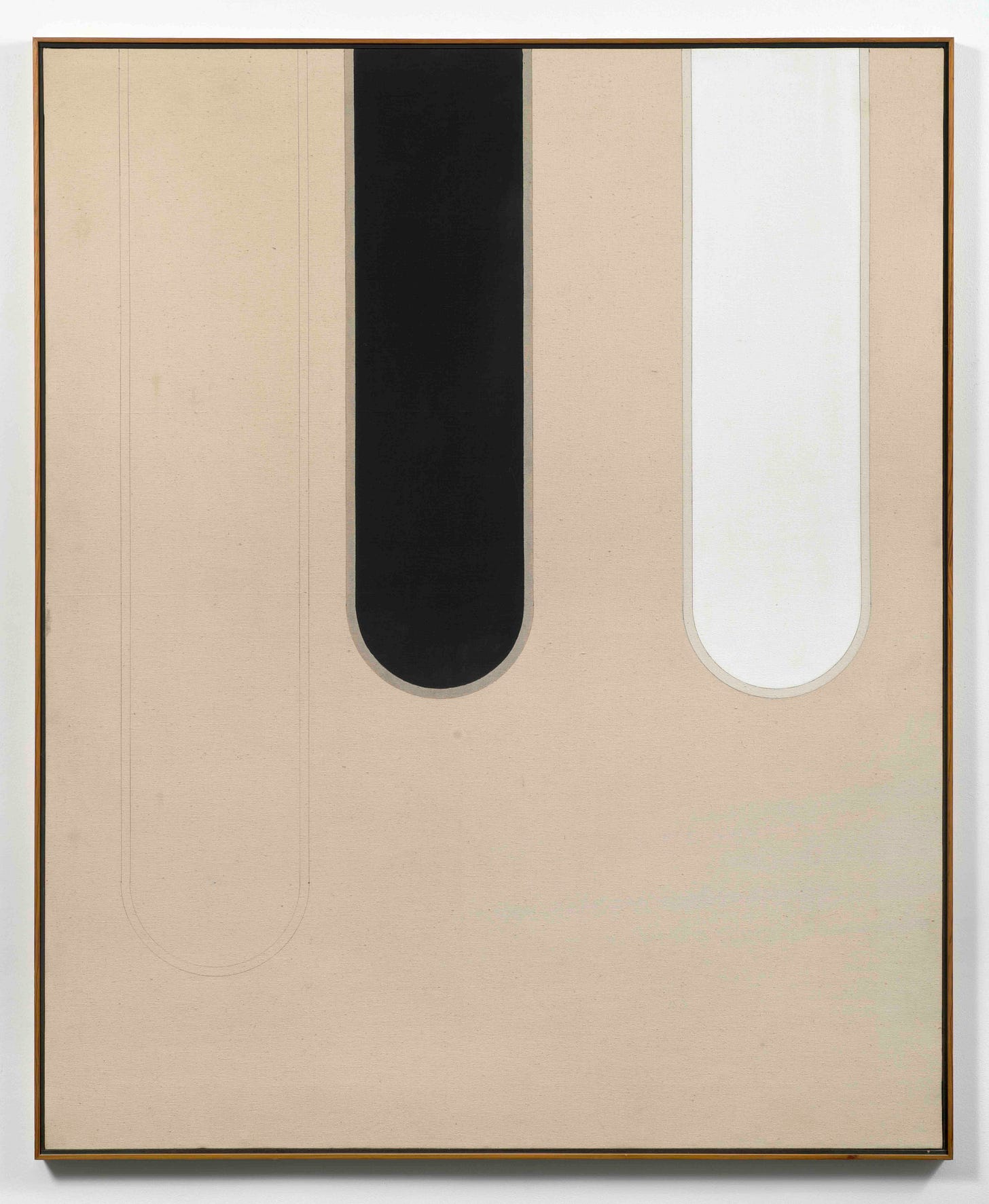

Thomas Downing, “Les Danseurs and The Water Glass” (Hemphill Artworks)

RED, PURPLE, AND GREEN ARE AMONG THE FEATURED COLORS that go unmentioned in the title of “Black, White and...,” a 10-artist exhibition at Hemphill Artworks. But the show’s most consistently intriguing hue is one that does get billing. Subtly assorted and variously textured, whites quietly upstage black in several of these pieces.

The show opens with three Mark Kelner paintings that neatly fuse his interests in art history and consumer culture by reducing notable 19th and 20th-century canvases to barcodes. The artist playfully delineates pictures by Gauguin, Picasso, and Barnett Newman, but the pictures aren’t as flat as the UPC on a bag of Doritos. Kelner thickly applies the white pigment beneath the black lines, and gently textures it to produce swirls and peaks that play against the flattened images.

Tim Doud does something similar with his trio of black-and-white collage-paintings, dubbed “AWL studies.” The bold black forms are jumbled by cuts, and the white-acrylic fields are interrupted by small areas that are unpainted. These pictures, along with two more that are more akin to ink blots, can be seen as fragmenting or partway reconstructed.

Like most Hemphill group shows, this one includes entries by several Washington artists who emerged since 1950 and are now deceased. Among these offerings are the only white-free work, a bold 1967 Paul Reed geometric color-field painting whose two crossed bars are very dark but not quite black. Also in this category are Jacob Kainen’s unexpected “Mr. Kafka,” a near-Cubist black-and-white 1970 print, and William Christenberry’s untitled drawing made with a bundle of pencils (color as well as graphite) to produce a series of fluid but near-congruent gestures.

The Christenberry drawing fits neatly with recent mixed-media work by Amy Schissel and Anne Rowland. The former’s black-gray-and-white cartographic fantasias are sprinkled with tiny accents in multiple colors; the latter’s assemblages of satellite images yield abstract compositions, including one that’s overwhelmingly red.

The most minimal, and yet conceptually bold, item is a 1982 Thomas Downing painting of three parallel curved-end oblongs, one black, one white, and one simply outlined in pencil. Here the principal white is the expanse of ivory-hued unpainted canvas, untouched and yet seemingly pulsing with possibility. Downing makes white function as both absence and presence.

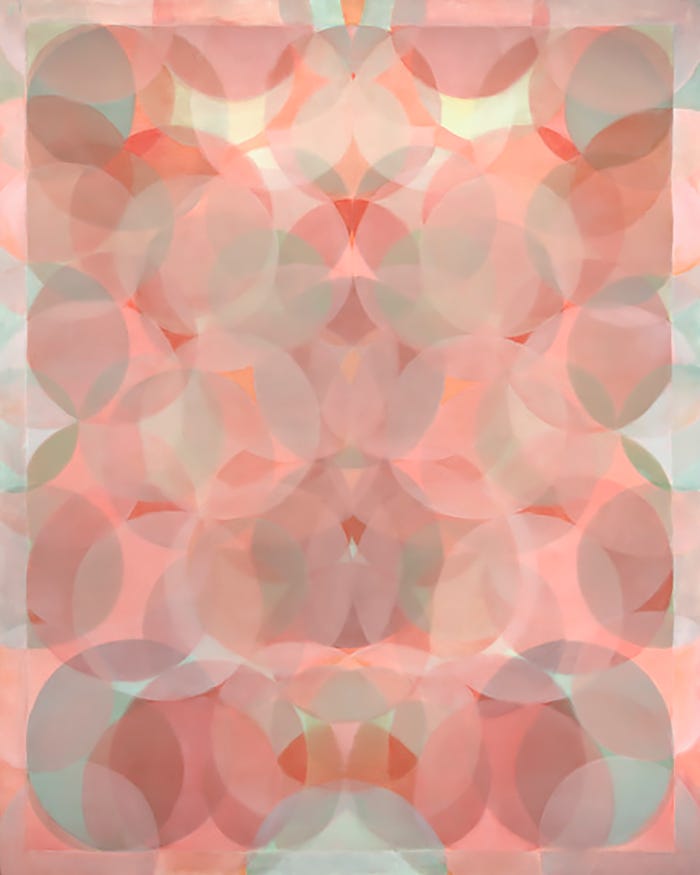

Jeremy Flick, “23-085” (PFA Gallery)

ONLY ONE OF THE ARTISTS IN PFA GALLERY’S “Operating System” is a sculptor, but all four conjure volume and depth. The contributors are geometric abstractionists who dabble in illusionism and optical effects to gently confound the eye.

Perhaps the most playful is Paola Oxoa, whose paintings center on a pair of circles that suggest eyes -- especially in “Around,” in which the circles are outfitted with pupil-like dots. (Perhaps it’s worth noting that the New York City area artist has a BFA in animation.) Straight lines span the pictures horizontally, while rubbery ones emanate vertically like a cartoon representation of radio waves. The center cannot hold, yet everything flows to or from it.

There’s also a sense of oscillating swells in Alex Puz’s pictures, in which lines in two hues overlap and interlock so tightly that the results suggest moire patterns. The Baltimore artist denotes his paintings’s elemental color schemes on their sides, and then weaves the undulating forms intricately to simulate a shimmering rainbow.

Jeremy Flick constructs his paintings from four eccentric rectangles that appear to overlay like sheets of colored film, yielding blended hues. In fact, the Washington artist merely simulates the superimposition of the colors -- from two to as many as four -- meaning that his hard-edged pictures are executed with exceptional precision.

Bars of color characterize Michael Scott’s work, but his lines are painted in enamel on T-shaped metal towers, the tallest nearby six feet tall. The New Yorker’s sculptures slightly resemble Anne Truitt’s, but feature hotter hues and more spindly shapes. Scott is essentially drawing vertical lines in space, pushing strategies all four of these artists pursue into a third dimension.

Mira Hecht, “Radiance” (Mira Hecht)

OVERLAPPING IS CRUCIAL TO MIRA HECHT’S PAINTINGS, yet the compositions often don’t seem to get denser as the local artist layers circles, soft-edged and porous, upon circles. The title of Hecht’s ADA Gallery show, “Light Works,” is apt. These pictures seem to glow from within or from someplace beyond, like diaphanous curtains that admit most of the sunlight from outside. At their faintest, the diluted-oil paintings seem partly bleached, as if illumination is in the process of burning away all the pigment, leaving nothing but enveloping whiteness.

This show will look familiar to anyone who saw Hecht’s exhibition at the American University Museum a year ago. One difference is that this selection features more drawings, including two recent ones whose style is looser and sketchier, yielding forms that appear floral rather than prismatic. There’s also a striking older piece, “Intangible Veil/Vibrance,” that arrays barely-there pastel rounds on a faint but methodical grid of delicate pencil lines.

The largest painting, “Radiance,” is built up from levels of red and gray-blue circles, with hints of yellow. Like most of the artist’s pictures, it’s center-focused yet not precisely symmetrical, so it conveys a sense of spontaneity within order. Made from similar ingredients yet almost shockingly divergent is “Dawn,” in which green, blue, and purple circles cluster below a upper-left color field so dark it’s almost black. Amid all these noonday works, finding this nocturne is a pleasing jolt.

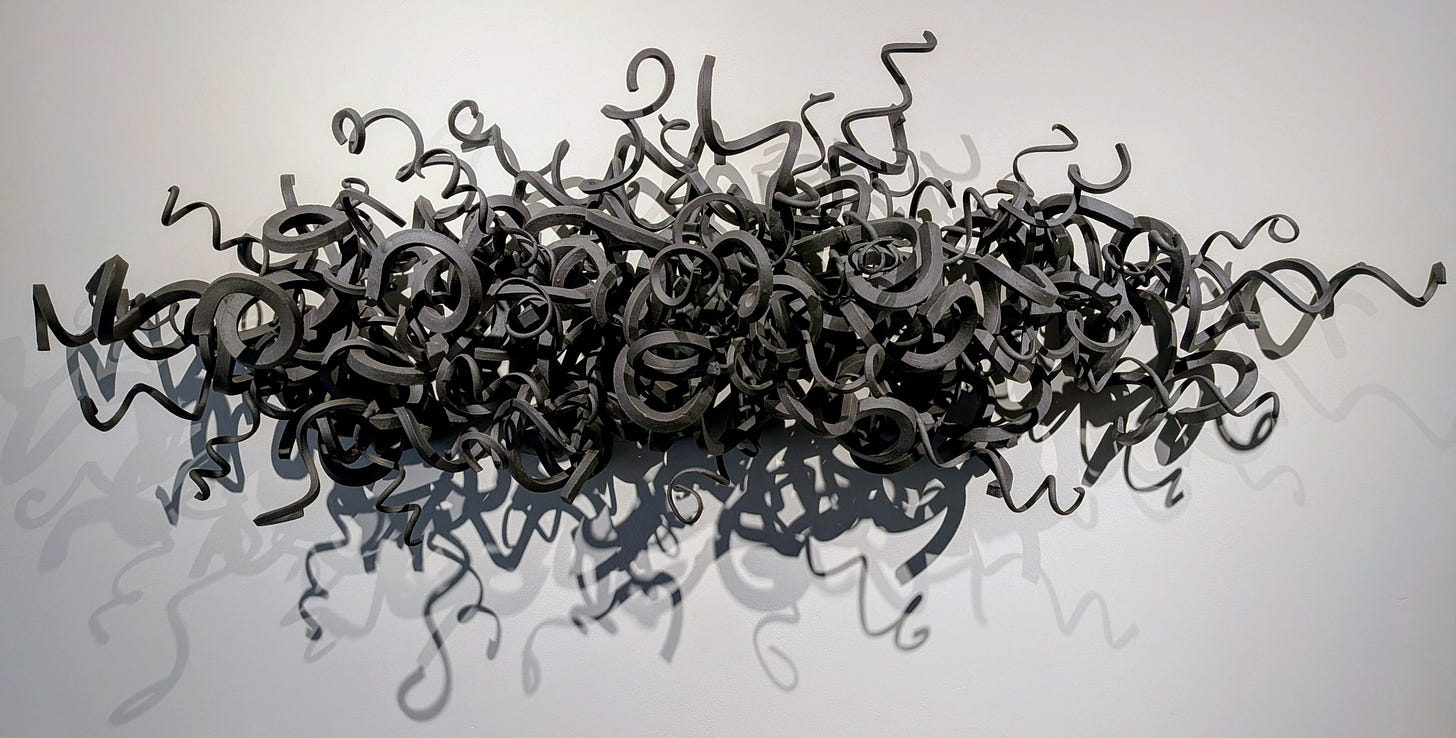

Laurel Lukaszewski, “Dark Energy” (photo by Mark Jenkins)

THE JUXTAPOSITION OF DELICACY AND POWER is the crux of Laurel Lukaszewski’s “A Fragile Strength,” an array of formally inventive stoneware and porcelain. Six months ago, the suburban-Maryland artist showed animal-themed pieces, rendered in glass and ink as well as ceramics, at Artists & Makers. Some works in her current Portico Gallery exhibition incorporate spiky forms that suggest sea urchins. But most are formal abstractions that toy elegantly with strands and links, and with various ways to position solid objects in midair.

One other element is vital if indirect: shadow. Whether Lukaszewski has arranged ceramic threads into jewelry-like chains or thicket-like clusters, the resulting pieces cast intricate vestiges on the wall behind them. The visual echo of “Night Echo” is the lattice projected on the adjacent surface, and part of the energy of “Dark Energy” emanates from the shifting, overlapping patterns it yields. The grayness of these shadows complements the palette of the show, which is mostly black, white, or something in-between.

There are some gray-blues, which tend to fade to white, as well as a few touches of pink. Another variation on the show’s typical mode is a piece that repeatedly writes the word “fragile” in porcelain slip, with a pile of letters below a dangling lanyard of words. Usually, though, Lukaszewski doesn’t need to spell out her ideas. Her titles invoke such natural forces as wind and a waterfall, but here the artist’s hand is the prime mover.

Installation view of Tae Hwang’s “Big Value” (Black Rock Center for the Arts)

THE IRONY OF TAE HWANG’S “BIG VALUE” is that the Baltimore artist’s treatment of American abundance is quite spare. In Black Rock Center for the Arts’s principal gallery, Hwang is showing a single painting -- one that is, admittedly, 12 feet high -- and two simple text pieces, notably a huge “99¢” in red. The main event upstairs is a grid of roughly 100 small drawings, paintings, and collages, all on the subjects of food and food merchandising. Also in the second-floor gallery are a customized gumball machine and an oversized simulation of a fortune-cookie maxim that likens freedom to a bargain price for hot dogs.

The crucial backstory is that as a child Hwang stocked shelves in a small grocery store run by her Korea-born parents. That might explain her interest in the ads and coupons she cuts into collages. Another irony: These small pictures can be appreciated only by close viewing, but some of them are mounted too high on the wall to be legible. Again, the presentation undermines the sense of consumer-culture bounty.

The fruits, vegetables, and various kinds of junk food in the 12-foot-high painting, “Still Life (Grocery Series),” are much easier to comprehend. Yet in this picture the artist uses a different approach to undercut the voluptuousness of the mass-marker cornucopia: The painting is rendered in black-and-white, so that the alluring hues of grapefruit, cupcakes, and the rest are hidden. Everybody has to eat, but Hwang is determined to make American foodways look less appetizing than they do in supermarket ad inserts.

Black, White and...

Through Dec. 20 at Hemphill Artworks, 434 K St. NW. hemphillfinearts.com. 202- 234-5601.

Operating System

Through Dec. 20 at PFA Gallery, 1932 9th St. NW (entrance at 1917 9 1/2 St. NW). pazofineart.com. 571-315-5279.

Mira Hecht: Light Works

Through Dec. 20 at ADA Art Gallery, 1627 21st St. NW. adawdc.org/en/page/13/culture. 202-621-6633.

Laurel Lukaszewski: A Fragile Strength

Through Dec. 20 at Portico Gallery, 3807 Rhode Island Ave., Brentwood. portico3807.com. 202-487-8458.

Tae Hwang: Big Value

Through Dec. 18 at Black Rock Center for the Arts, 12901 Town Commons Dr., Germantown. blackrockcenter.org. 301-528-2260.