Star Maps

Charting Australian Aboriginal art at the National Gallery of Art, Embassy of Australia, and Amy Kaslow Gallery. Also: Ron Meick’s body-conscious prints

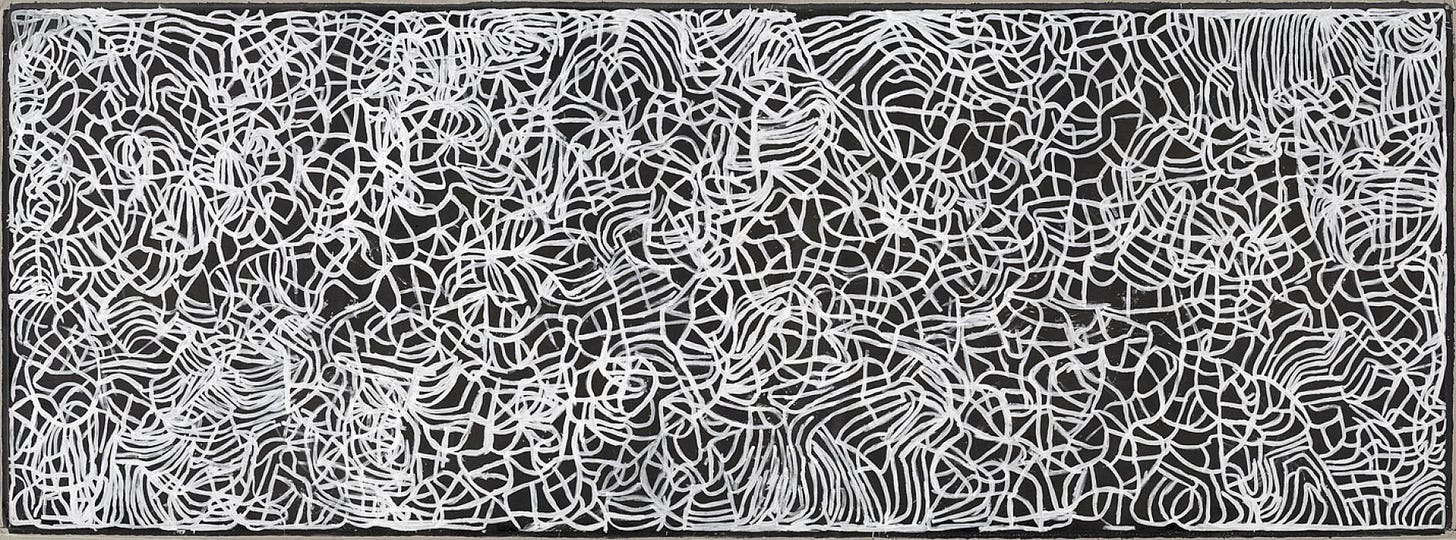

Emily Kam Kngwarray “Anwerlarr Anganenty (Big Yam Dreaming)” (National Gallery of Art)

NEAR THE ENTRANCE TO “THE STARS WE DO NOT SEE: Australian Indigenous Art” stands a grove of painted eucalyptus trunks and bark paintings, standard components in exhibitions of Australian Aboriginal art. Such embellished trunks featured, for example, in the Aboriginal women’s art show at the Phillips Collection in 2018. But adjacent is something unexpected: Reko Rennie’s images of two warriors, outlined with neon-lighted tubes that glow blue or pink, respectively. The contrast of ancient and modern sets the tone for this expansive National Gallery of Art show, which was organized with the National Gallery of Victoria and curated by Myles Russell-Cook. It’s advertised as the largest exhibition of Australian Indigenous and Torres Strait Islander art ever shown in North America.

Australian Indigenous and Torres Strait Island culture -- or cultures, since there many variations -- is reputedly among the oldest on Earth. Some examples of rock carving and painting and other art forms on the continent are millennia old. But the Indigenous art shown in museums and galleries today is nearly always recent, the result of introducing European-style materials and pigments during the 20th century. While some contemporary Aboriginal artists still employ earth-based pigments, most use acrylics.

The show’s title is derived in part from the work of Gulumbu Yunupinu, who became a celebrated artist during a relatively brief career. (She didn’t start painting until she was 56.) The selection includes three of her bark paintings, which represent the vast, twinkling heavens over northern Australia. What appear to be star-choked skies are common motifs in this show’s all-over paintings, although the highly stylized depictions can also be read as cracked earth, reptile skin, or maps of hallowed places that -- like those stars -- cannot actually be seen. Typically, these abstracted scenes are shown as if beheld from above, which leads some observers to describe the pictures incongruously as “aerial views.”

Other notable landscape -- or landscape-inspired -- paintings include Emily Kam Kngwarray’s “Anwerlarr Anganenty (Big Yam Dreaming),” a nine-foot black-and-white imagining of roots beneath the surface, as well as a large picture of a salt lake executed collectively by 12 women. The lake is rendered mostly as a white void, flanked by 29 small blue circles that each represent a sacred water-hole in the East Pilbara region.

A few pictures made in a fairly traditional style are more literal. The “Minh spirits” who dance or fight in Bardayal Nadjamerrek’s paintings are identifiably humanoid, and the insects and plants in Dhambit Munungurr’s blue-and-white bark painting are loose but recognizable. One of the show’s highlights is a rare linocut, Alick Tipoti’s “Zugubul,” in which eight sailors, trailed by flying pelicans, navigate a large canoe across an ocean that’s as intricately patterned as any of the exhibition’s land- or skyscapes.

The last gallery is devoted to “Indigenous Futures,” but the future has already seeped into some of this work before the show expands to encompass photography, video, and conceptual art that addresses racism and Indigenous identity. Albert Namatjira’s 1940s realist watercolor landscapes, skillful and conventional, were condemned as “assimilated.” While Paddy Bedford’s 2000 painting of a glyph on a field divided between white and red looks more traditional, its depiction of a single figure rather than a teeming whole suggests Western influence.

One of the “future” pieces is Tony Albert’s “History Repeats,” which spells out that phrase three times in found letters and other artifacts. The first “i” is, playfully, a boomerang. But it’s probably more significant that the first and last “t” is each a Christian cross. Including these symbols is a reminder that Western colonizers have reshaped Aboriginal culture in a lot more substantial ways than simply by providing acrylic paint.

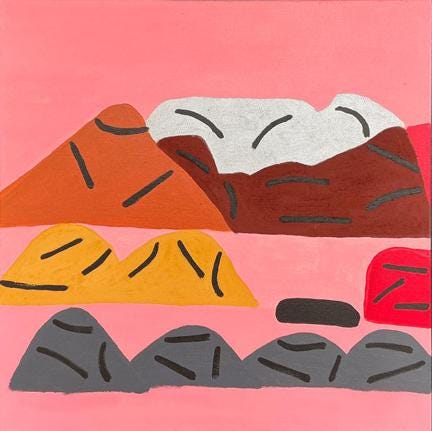

Evelyn Magil, “Winuba” (Embassy of Australia)

ALTHOUGH IT EXPLORES THE ART OF A SMALL REGION, “All That Country Holds: Art from the Kimberly” is impressively diverse. Painting dominates, but this Embassy of Australia show also includes photography and ceramics. And while the painting can be on such traditional materials as bark and kangaroo skin, there are also sets of pictures daubed on cowboy hats and on 3D-printed simulations of cow skulls.

The 10 contributing artists are all Aboriginal people from Kimberley, the northernmost district of the state of Western Australia. This area is tropical and remote; it’s much closer to East Timor than to Sydney, Melbourne, and Canberra. Part of Kimberley is cattle country, which explains the renderings of cows and cowboys, as well as the use of cowhide as a medium for painting.

The selection includes the expected pattern paintings, compositions of dots, triangles, and curved lines that represent both actual and symbolic landscapes. But a surprisingly large percentage of the imagery is fully representational. John Prince Siddon punctuates stylized map paintings with recognizable animals, Mervyn Street realistically portrays men who wrangle cattle through a red-rock landscape, and Evelyn Malgil depicts similar terrain with black-outlined forms that give her vividly hued pictures a pop-art vibe.

While most of the paints are acrylic, some of the most striking pictures were made with traditional earth-based pigments. These give a sense of depth and complexity to Leah Rinjeewala Umbagai’s elegantly mottled “Burnaddee,” whose images are modeled on cave paintings, and Jan Baljagil Griffiths’s “Our Connection,” whose flattened tree branches are festooned with painted porcelain facsimiles of baob nuts attached to the ocher-painted paper. The artist’s use of porcelain -- like Siddon’s 3D-printed skulls or portraitist Mary-Lou Orliyarli Divilli’s camera -- exemplifies the ambition of these artists. “All That Country Holds” is rooted in a specific place, but reaches well beyond it.

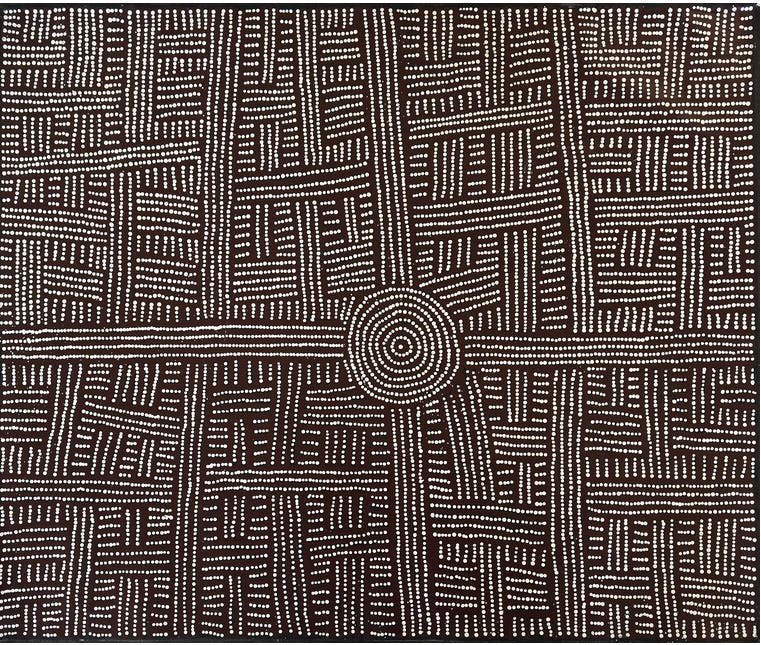

Bambatu Campbell Napangardi, “Womens Ceremony” (Amy Kaslow Gallery)

AMONG THE TRADITIONAL PICTORIAL FORMS that Aboriginal artists have recently transferred to canvas is body painting. A fine example of this is the white-on-black patterning in paintings by Betty Mbitjana, one of the nine contributors to Amy Kaslow Gallery’s “Songlines: Contemporary Aboriginal Masters.” All are Papunya People from Australia’s Central Desert. They include such founders of Papunya contemporary art as Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri and Turkey Tolson Tjupurrula, who in 1971 began transferring native imagery from sand-drawing to the more permanent medium of acrylic paint.

Most of the pictures are symbolic landscapes rendered with parallel lines and closely spaced dots. These can be as spectacularly psychedelic as Gabriella Possum Nungurrayi’s mostly multi-colored compositions, which include blue accents rare in Aboriginal art. Her paintings evoke both Persian carpets and skies full of fireworks, since explosion-like bursts punctuate the densely knitted fields. Many of the other pictures are just as tightly meshed, but nearly Cartesian in design. Tjupurrula’s earth-toned paintings are packed with interlocked rectangles, and Bambatu Campbell Napangardi’s “Womens Ceremony” abuts dotted lines in a manner that suggests beadwork.

That these artists are attuned to movement in the natural world is underscored by the titles of such pictures as William Sandy’s “Dingo Trials” and Julie Nangala Robertson’s “Water Dreaming.” There’s a different sort of physicality to Mbitjana’s “Body Paint - Bush Melons,” whose watery white gestures appear finger-painted. Even if the black field beneath the white loops is not actual skin, the way Mbitjana applies pigment embodies her continuity with Aboriginal artists whose only available surfaces were rock, sand, and flesh.

Ron Meick, “Red Eye” (Washington Printmakers Gallery)

THE PICTURES IN RON MEICK’S SHOW at Washington Printmakers Gallery may look like the work of a minimalist, but the Delaware artist presents himself as a storyteller. The little tales spun by “Short Stories” often involve damage, sometimes of Meick’s own body. Thus “Red Eye” and “Black Eye,” two squashed ovals rendered in the titular colors. Their forms appear elementary, but their implications are complicated -- and vicariously painful.

Assuming, that is, that the commentary about how stress reddened and a blow blackened Meick’s eye is reliable. The artist used an AI program to compose the show’s notes, and while they’re coherent, some of what seems informative may actually be hallucinatory.

The “Eyes” are lithographs that simulate the qualities of drawing, heavily worked at the ovals’s centers and softly smudgy at the borders. The seemingly freehand images demonstrate Meick’s mastery of lithography, but that’s not his only method. The show also includes monotypes combined with relief prints and a single woodcut, “Woven Orientation,” that’s exhibited along with its matrix, positioned at a 90-degree angle to the wall that holds the print.

A playful exercise in form, “Woven Orientation” consists of four continuous lines -- blue, red, green, and yellow -- that loop around and atop each other. More characteristic, however, are fractured accounts of injuries, whether documented in a dental X-ray or the pieces of Meick’s father’s broken saxophone, which the artist inked and pressed against paper. The damage recorded by “Last Call from a Broken Home” is actual, and the use of the mutilated instrument to memorialize its own destruction is satisfyingly literal.

Where the horn print marries its subject and its medium, the twinned monotypes titled “Two of the Same Skin” are more metaphorical. After printing crumpled paper inked with peach-colored pigment, the artist displays both the 2D print and 3D matrix, which are as similar as they are distinct. Meick can employ pigment and paper to evoke the body, but he can also underscore the corporeal qualities of his materials. Ink and blood, paper and skin -- they’re not interchangeable, but they are interconnected.

The Stars We Do Not See: Australian Indigenous Art

Through March 1 at the National Gallery of Art, Sixth St. and Constitution Ave. NW. www.nga.gov. 202-737-4215.

All That Country Holds: Art from the Kimberly

Through March 26 at Embassy of Australia, 1601 Massachusetts Ave. NW. usa.embassy.gov.au/allthatcountryholds-kimberley. Open by appointment.

Songlines: Contemporary Aboriginal Masters

Through Dec. 14 at Amy Kaslow Gallery, 7920 Norfolk Ave., Bethesda. amykaslowgallery.com.

Ron Meick: Short Stories

Through Nov. 30 at Washington Printmakers Gallery, 1675 Wisconsin Ave NW. washingtonprintmakers.com. 202-669-1497.