Classical Twists

Virginia Van Horn's sculptures and Devin Ratheal's paintings bend classical and Renaissance art. Also: work by Elisabeth Jacobsen, Julie Paez, Kate Childs Graham, Philippe Ricard, and Alex Puz

Virginia Van Horn, “Echo” (photo by Mark Jenkins)

CLASSICAL EUROPEAN ART IS RESHAPED, LIQUEFIED, and crimped into loops by two artists showing separately at IA&A at Hillyer. Virginia Van Horn makes roughly life-sized horse sculptures from an abundance of materials, both traditional and modern. Devin Ratheal partly melts the imagery of neoclassical religious canvases, subjecting Biblical scenes to both computer distortion and a Futurist-style sense of movement.

Van Horn, a Norfolk artist, was inspired to make the three pieces in "Palindromes" by her equestrian childhood and a stint at the American Academy in Rome. That institution's emblem is the two-headed Janus, who gazes simultaneously into the past and the future; he's the god of beginnings (as in the month of January) and endings. Thus Van Horn's expertly crafted steeds have heads at both ends, which can denote both wisdom and uncertainty. When every direction is forward, there's no way to choose a path.

All three beasts are mostly wooden and stand on boat-shaped black plinths, but are otherwise rather different. The upraised legs and hooves of the galloping "Follow the Moon Horse" are outlined in bluish-white neon. The twin heads of the white-and-black "Echo" are encased in clear acrylic, contemporary and clinical. Tranquil yet wildest of the three, "Bramble" can be glimpsed only through a wooden thicket. The horses, stylized but fundamentally realistic, can be read as symbols yet have a naturalistic appeal.

This suits Van Horn's purpose. One of her goals is to explore "modern life in a way that illuminates the intimate collection between the human and the animal kingdoms," explains her statement. She's interested in the untamed animals -- like Bramble, perhaps -- who live in close proximity to residents of suburbia. Yet the artist's horses also seem archetypal, creatures of thought as much as wood. They have mythic as well as actual presence.

Devin Ratheal, “European Substrate” (photo by Mark Jenkins)

As busy as Van Horn's sculptures are sleek, Ratheal's pictures are swirling action paintings in which both the subjects and the styles seem to be in motion. The surfaces teem with so much activity that the commotion spurts off the canvas into ribbons of abstracted imagery. The Texas artist abhors a vacuum, so he fills every bit of the composition and cuts out the rest, yielding elaborately shaped canvases that can encompass dozens of curving edges. The results recall Bosch and Brueghel, as well as Jack Kirby-era Marvel comics.

Raised in a nonreligious family, Ratheal sees Renaissance and Baroque religious paintings as subjects for investigation rather than veneration. He experienced such pictures as "eerie" and "alien," according to his statement. His response was to make them more so, warping and layering the originals digitally and then expertly painting the composites in a traditional mode, with oil on wooden panels. If the effect appears strange, that's intentional. Ratheal takes a religious worldview that was once dominant and mainstream and deforms it into something inexplicable. Which, he seems to argue, it was all along.

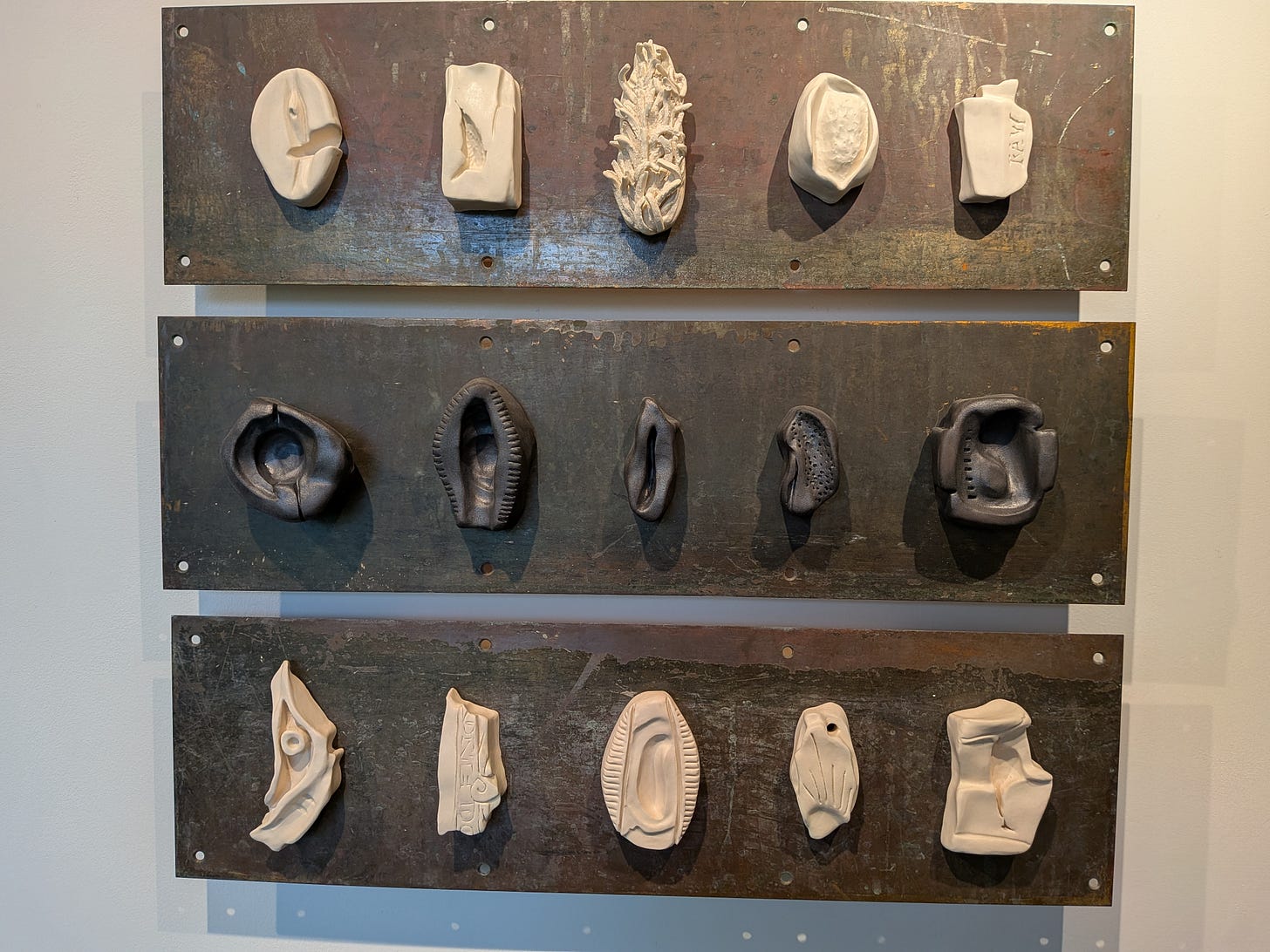

Kate Childs Graham, "Vulvas -- the objects we find" (photo by Mark Jenkins)

TWO OF THE PARTICIPANTS IN PORTICO GALLERY'S CURRENT SHOW put things together, while the third takes them apart. The latter undertaking yields the most provocative art, since the entity ruptured by Kate Childs Graham (aka KCG) is the female body.

The most direct works in "Portico Pride: Resilience to Radiance" are Elisabeth Jacobsen's "Joy Sticks," four arrays of found bamboo slats of varying lengths, painted with patterns separated by areas of color. Each of the New York artist's sets is in hues derived from the pride flag, and is keyed to such themes as "community."

Rather more complicated are Julie Paez's assemblages, built mostly of natural items but sometimes incorporating human-made things, usually worn or battered. The D.C. artist's constructions contrast randomness and order, whether using manufactured pieces to contain fragments of nature or doing the opposite. Most strikingly, she employs four log slices, their centers rotted out, as frames for groupings of objects that range from pine cones to flower-like sculptures of collaged metal parts. Nature is primary, even when the materials are forged rather than found.

Detached body parts are prominent in KCG's intriguing work, often suggesting violent medical procedures, but sometimes apparently signifying objectification of women. "Surgery" mounts disembodied breasts on a rusty saw, hinting at an experience also evoked by a stark metal sculpture of chest scars. Yet the local artist also presents a vending machine full of plastic orbs, each containing a small breast -- tokens of commodified sex, perhaps.

Other corporeal bits on display include a quartet of umbilical cords and the small ceramic shapes of "Vulvas -- the objects we find." These 15 forms, 10 ivory and five black, are too abstract and various to literally represent genitalia. Perhaps they're meant to indicate that the body is echoed everywhere, from mollusks to seed pods. The human figure exists more within than outside its environment.

Philippe Ricard, “Who Cares If We Get Caught?” (Washington Printmakers Gallery)

WINDOWS ARE BOTH PORTALS AND TRANSITION POINTS in Philippe Ricard's frisky prints of Baltimore, his adopted hometown. Originally from suburban California, Ricard moved east to study printmaking at the Maryland Institute College of Art. There he mastered multiple processes, as he demonstrates in "Attached Observer," his Washington Printmakers Gallery show. The artist's style is boisterously cartoonish, but his technique is subtle and refined.

Most of these prints mix various printing processes, including etching and aquatint, occasionally supplemented by colored pencil. There are also four monotypes that appear softer and more painterly, although not necessarily less detailed. The more complex of them, "The Voyeur" and "Mutt Fleeing Surveillance," depict urban scenarios that are as elaborately fantastic as any of Ricard's more tightly rendered pictures.

The playfulness of "The Voyeur" is as much narrative as it is stylistic. A man reads a book, oblivious that behind him a woman can be seen undressing in a building across the street. His room's large windows face a set of nine smaller ones in which the women's actions, interspersed with the movements of a cat, transpire chronologically as if the windows are actually frames in a comic strip. The city is a sort of storybook.

None of Ricard's subjects are voyeurs. "Delirium at the Intersection" portrays one of Baltimore's controversial squeegee wielders, but more often the artist's characters turn away from the window, whether to make out inside a car or gaze at other passengers on a train. What they're missing is the spot where light shifts, and thus color schemes change, evoking an entirely different mood. In Ricard's prints, every window can open onto a new world.

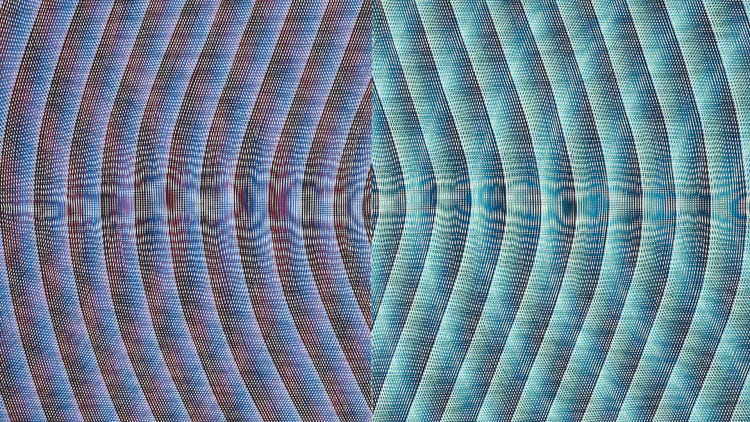

Alex Puz, “Trichomacy (Red-Green)” (Pazo Fine Art)

THERE WOULD BE A SCIENTIFIC VIBE TO ALEX PUZ'S PAINTINGS even if they weren't accompanied by the Baltimore artist's diagrammatic drawings of how colors affect the eye and the brain. The title of Puz's show at Pazo Fine Art's Kensington location is "Trichromacy," which refers to the process in which three independent channels, derived from the human retina's three different kinds of cone cells, simultaneously send signals from the eye to the brain.

The artist's style recalls Bridget Riley's 1960s op art, but is denser, more intricate, and less dependent on simple illusionist effects. In Puz's pictures, overlapping ripples of flashe vinyl acrylic pigment roll across canvas, yielding patterns that are both repetitive and contrapuntal. The crisp, systematic abstractions suggest radio waves, cerebral pulses, and photographic moire patterns.

The 12 pictures offer variations on a few motifs. Three in the "Island of Self Presence" series feature vertical lines that deflect in sync toward the bottom of the composition. The horizontal gestures in a pair of "Psychache" paintings curve in opposite directions, one ascending and one descending. Most direct, and often most effective, are the four titled "Chromatic Instinct" (plus their respective color combinations in parenthesis). The designs in these paintings are so regular that the eye gazes past and -- seemingly -- within them. Where Puz's biomechanical drawings are full of action, the "Chromatic Instinct" paintings are meditative. They demonstrate how the active experience of color can approach stillness.

Virginia Van Horn: Palindrome

Devin Ratheal: Peel of the Real

Through July 27 at IA&A at Hillyer, 9 Hillyer Court NW. athillyer.org. 202-338-0680.

Portico Pride: Resilience to Radiance

Through July 26 at Portico Gallery, 3807 Rhode Island Ave., Brentwood. portico3807.com. 202-487-8458.

Philippe Ricard: Attached Observer

Through July 26 at Washington Printmakers Gallery, 1675 Wisconsin Ave NW. washingtonprintmakers.com. 202-669-1497.

Alex Puz: Trichromacy

Through July 26 at Pazo Fine Art, 4228 Howard Ave., Kensington. pazofineart.com. 571-315-5279.